Reagan Has Space Shuttle to Orbit Again to Sleep Lie by Dems

Wh en humans motion to infinite, we are the aliens, the extraterrestrials. And and so, living in space, the oddness never quite goes away. Consider something equally elemental as sleep. In 2009, with the expansive International Space Station nearing completion after more than than a decade of orbital construction, astronauts finally installed some staterooms on the U.S. side—four individual cubicles virtually the size of plane lavatories. That's where the NASA astronauts slumber, in a space where they can close a folding door and have a few hours of privacy and repose, a few hours away from the radio, the video cameras, the instructions from Mission Command. Each cabin is upholstered in white quilted material and equipped with a sleeping pocketbook tethered to an within wall. When an astronaut is ready to sleep, he climbs into the sleeping bag.

"The biggest thing with falling asleep in infinite," says Mike Hopkins, who returned from a half-dozen-month tour on the Infinite Station last March, "is kind of a mental matter. On Earth, when I've had a long day, when I'one thousand mentally and physically tired—when you get-go lie down on your bed, there'due south a sense of relief. You get a load off your feet. There's an immediate sense of relaxation. In space, y'all never feel that. Y'all never have that feeling of taking weight off your feet—or that emotional relief." Some astronauts miss information technology enough that they bungee-string themselves to the wall, to provide a sense of lying down.

Sleep position presents its ain challenges. The primary question is whether you lot desire your arms inside or outside the sleeping bag. If you leave your artillery out, they float costless in zero gravity, oftentimes globe-trotting out from your body, giving a sleeping astronaut the look of a wacky ballet dancer. "I'm an inside guy," Hopkins says. "I like to exist cocooned upward."

Hopkins says he didn't have unusual dreams in space, although at present, back on Earth, he does occasionally dream of floating through the station. "I wish I dreamed every night of floating," he says. "I wish I could recapture that."

Spaceflight has faded from American consciousness even every bit our performance in infinite has reached a new level of accomplishment. In the by decade, America has become a truly, permanently spacefaring nation. All 24-hour interval, every day, half a dozen men and women, including two Americans, are living and working in orbit, and take been since November 2000. Mission Control in Houston literally never sleeps now, and in one corner of a huge video screen there, a counter ticks the days and hours the Space Station has been continuously staffed. The number is rounding past 5,200 days.

It's a picayune strange when you lot think about it: Just near every American ninth-grader has never lived a moment without astronauts soaring overhead, living in infinite. But chances are, nearly 9th-graders don't know the name of a single active astronaut—many don't even know that Americans are upward there. Nosotros've got a permanent space colony, inaugurated a twelvemonth before the setting of the iconic movie 2001: A Infinite Odyssey. It'southward a stunning achievement, and it's completely ignored.

As a culture, we remain fascinated by the possibilities, discoveries, of infinite travel. The 2013 picture Gravity, starring Sandra Bullock and George Clooney, brought in $716 one thousand thousand at the box office and won seven Academy Awards. Merely we seem indifferent to what is happening in reality all the time now. Without any fanfare, we have slipped into the era of Captain Kirk and Mr. Spock. We just know the fictional characters ameliorate than the real ones. Mayhap that'south unsurprising. The Space Station is an engineering curiosity, simply all it seems to do is soar in circles—a fresh sunrise every 92 minutes. Scientific enquiry on the station hasn't yielded whatever noteworthy breakthroughs, and daily life there, thankfully, lacks the drama of a movie script.

But all of that does the station and its astronauts a disservice: The details and challenges of life in space are weird and arresting, revealing and valuable. In them, one tin begin to make out a greater purpose for the station'southward 82,000 manned orbits—even if it's not the one NASA seems to be pursuing.

The International Infinite Station is a vast outpost, its calibration inspiring awe even in the astronauts who have synthetic information technology. From the border of ane solar panel to the edge of the contrary one, the station stretches the length of a football field, including the end zones. The station weighs nearly ane million pounds, and its solar arrays cover more than an acre. It's as large inside every bit a half-dozen-sleeping accommodation firm, more than ten times the size of a space shuttle's interior. Astronauts regularly volunteer how spacious it feels. It's so big that during the early years of three-person crews, the astronauts would often go whole workdays without bumping into one another, except at mealtimes. Indeed, it'south so big, you lot can come across information technology tracing across the nighttime sky when it passes overhead (there are apps for finding information technology, ISS Spotter amidst them).

The station is a joint operation: half American, half Russian, with each nation managing its own side of the craft (the U.S. side includes modules or equipment from Canada, Japan, and Europe, and typically a visiting astronaut from one of those places). Navigation responsibilities and operation of the station's infrastructure are shared, and the role of station commander alternates between a cosmonaut and an astronaut. The Russian and U.S.-side astronauts typically proceed to their own modules during the workday. Only the crews often gather for meals and hang out together after work.

As a facility, a spacecraft, and a dwelling house, the station is most comparable to a transport. It has its ain personality, its own charms and quirks. Coiffure members come and become, bringing their own style, just the station itself imposes a sure rhythm and tone. It has a more than sophisticated water-recycling system than whatever on World. An astronaut who mixes up an orangish drink for breakfast on Monday morn and urinates on Monday afternoon tin can use that aforementioned water, newly purified, to mix a fresh drink on Th. Yet the station lacks a refrigerator or freezer for food (at that place is a freezer for science experiments), and while the food is much better than it was 20 years ago, most of it's all the same vacuum-packed or canned. The arrival of a few oranges on a cargo send every couple of months is crusade for jubilation.

On the station, the ordinary becomes peculiar. The do bike for the American astronauts has no handlebars. It also has no seat. With no gravity, it's only as like shooting fish in a barrel to pedal furiously, feet strapped in, without either. You tin can lookout a movie while you pedal by floating a laptop anywhere you want. But station residents have to exist conscientious about staying in i place likewise long. Without gravity to help circulate air, the carbon dioxide yous exhale has a tendency to form an invisible cloud around your caput. Y'all can end upwards with what astronauts call a carbon-dioxide headache. (The station is equipped with fans to help with this problem.)

Since the station'due south first components were launched, 216 men and women have lived at that place, and NASA has learned a lot about how to live in space—near the difference between rocketing into zilch‑Chiliad for 2 weeks and settling in for months at a time. Day-to-solar day life in infinite is nada like the sleek, improvisational earth that Telly and flick directors take created. It is more thrilling and dangerous than we earthlings appreciate, and besides more choreographed and mundane. Frequently those qualities coexist in the very same feel, such as spacewalking. Space is a brittle and unforgiving place—a single thoughtless maneuver can trigger disaster. NASA has reduced the hazard past scripting almost everything, from the replacement of a water filter to the safety checks on a infinite suit. In 54 years of flight humans in space, NASA has suffered three fatal spacecraft accidents that killed a total of 17 people—the Apollo ane capsule fire in 1967, the Challenger shuttle disaster in 1986, and the Columbia shuttle disaster in 2003. But none of those resulted from any fault on the function of the astronauts. The meticulous scripting can make watching the astronauts at work boring, but NASA knows that excitement means mistakes.

Even by the depression estimates, it costs $350,000 an hour to go on the station flying, which makes astronauts' time an exceptionally expensive resources—and explains their relentless scheduling: Today's astronauts typically first work past 7:30 in the morning, Greenwich Mean Time, and terminate at 7 o'clock in the evening. They are supposed to accept the weekends off, only Saturday is devoted to cleaning the station—vital, but no more fun in orbit than housecleaning downwards here—and some work inevitably sneaks into Sunday.

From 2003 to 2010, 10 American astronauts who lived on the station kept a diary equally role of a research study conducted by Jack Stuster, an anthropologist who studies people living in extreme environments. The bearding diaries—virtually 300,000 words in all—reveal people who are thrilled past life in space, and occasionally bored, and sometimes seriously irritated. For a nation accustomed to 50 years of grinning, can-practise astronauts who almost never say annihilation genuinely revealing about flight in infinite, the diaries are refreshingly frank.

"I had to laugh to myself at the procedures today," wrote 1 station astronaut.

To replace a low-cal bulb, I had to have safety glasses and a vacuum cleaner handy. This was in case the bulb broke. Yet, the actual bulb is encased in a plastic enclosure, and so fifty-fifty if the glass bulb did break, the shards would be completely contained. As well, I had to take a photograph of the installed bulb, before turning it on. Why? I have no idea! Information technology's just the way NASA does things.

Astronauts never tire of watching the Earth spin below—one wrote of stopping at a window and existence so captivated that he watched an entire orbit without even reaching for a camera. "I have been looking at the Earth, from the point of view of a visiting extraterrestrial," wrote another. "Where would I put down, and how would I go virtually making contact? The least dangerous thing would be to lath the International Infinite Station and talk to those people commencement."

The diary entries make information technology very clear that half-dozen months is a long fourth dimension to be in space—a long time to go without family unit and friends, without fresh food, without feeling sunshine or rain or the pleasures of gravity; a long time to exist tethered to the tasks of maintaining body and station, on a ship with no bathing or laundry facilities. The entries also reveal that keeping a diary significantly improves an astronaut'south morale.

During brusque missions, even ii-week shuttle missions, the excitement of beingness in space never fades. On the station, NASA and the astronauts themselves accept had to be more circumspect to morale, merely because at that place's a lot of work that's uninteresting. The Space Station has a telephone—astronauts tin can call anyone they want, whenever it'southward convenient—and their families get a specially programmed iPad for private videoconferences. The astronauts have private conversations with NASA psychologists once every two weeks. They also have regular conferences with NASA strength coaches—twice as oft equally they talk to the shrinks.

In space, says Mike Hopkins, "Everything is new. Simple hygiene, eating a meal, sleeping—you name it, it's all completely different from what yous're used to." That's from someone who, like nearly astronauts, trained full-time for ii years before launch, and then that he would know what to look.

The Space Station is stocked with movies and has a locker filled with paperback books. But Ed Lu, one of the earliest crew members, in 2003 decided that he wasn't going to spend his complimentary time doing something and then earthly as reading a paperback. "I don't know if I'm ever coming back here," Lu remembers thinking to himself. "I desire to practice things I can never do at home."

When Lu arrived at the Infinite Station—he was one-half of a 2-person coiffure that kept the station active in the wake of the Columbia disaster—he'd already flown two shuttle missions, and had 21 days' experience living in zip‑Yard. "I decided to learn to fly ameliorate, to acquire acrobatics," he says. "I would option a module and say to myself, Every fourth dimension I become through this module, I'm going to fly through without touching the sides. I would pick a compartment and say, Every fourth dimension I go through this compartment, I'm going to practice a double flip. Being on station was my third flight, and I idea I knew what I was doing. But I got an awful lot better with months of training."

The singular experience of space is the flight—non flight the spaceship y'all're in, but flight, yourself, inside it. That's what actually makes you an astronaut—not altitude, merely the most unbelievable liberation from gravity. Astronauts speak of information technology with bemused awe, considering information technology is pure delight but too totally counterintuitive and sometimes inconvenient.

"What'due south it like to alive in zero‑Grand?" asks Sandra Magnus, who took three spaceflights, including 130 days on the station, before her recent retirement from the astronaut corps. "Information technology's a lot of fun," she says, then bursts out laughing. "I learned to bear things with my knees—constrict them between my knees and shove off. That way I had my hands free to propel myself. The thing is, in space, Newton's laws rule your life. If you're doing something as simple every bit typing on a laptop, you're exerting force on the keyboard, and you finish up getting pushed abroad and floating off. You have to hold yourself down with your feet." Magnus developed calluses on her big toes because she used them continuously, in stocking feet, to navigate and position herself.

Gravity is an indispensable organizing tool, she says, one you don't appreciate until y'all accept to alive without it. "Just wait around the room you're in … At that place'due south stuff sitting on tables, on shelves, in drawers, on the floor. In infinite, all of that would be all over the place." Every unmarried item you use needs to be secured, or it volition float off. Astronauts mutter quietly near the amount of time they spend searching for misplaced equipment—"Keeping track of stuff can eat your whole twenty-four hour period," says the astronaut Mike Fincke—simply securing everything also takes time.

Magnus liked to cook for her colleagues on the station, finding new dishes to make with the food NASA supplied, especially with the commitment of, say, a fresh onion. "It takes hours, so I could merely do it on the weekend," she says. "Why hours? Think near 1 thing: when you cook, how often you throw things in a trash can. How can you lot practise that? Because gravity lets you throw things in the trash. Without gravity, you have to figure out what to do. I put the trash on a slice of duct tape—duct record is awesome—but even dealing with the trash takes forever."

When you're in null‑Yard, all the fluids in your body are in nada‑G likewise, and then astronauts often have a stuffy-head feeling, from fluid migrating to their sinuses; some stop up literally puffy-faced. And zero‑K causes the nausea and space sickness that many astronauts take quietly suffered during the showtime 24-hour interval or two in orbit, going dorsum at to the lowest degree to Apollo. Leroy Chiao, 54 and retired from the astronaut corps afterward four flights, describes what happens even earlier you lot float out of your seat. "Your inner ear thinks you're tumbling: the balance system in there is going all over the place … Meanwhile your optics are telling you lot y'all're not tumbling; y'all're upright. The two systems are sending all this contradictory information to your brain. That tin exist provocative—that's why some people experience nauseous." Within a couple of days—truly miserable days for some—astronauts' brains learn to ignore the panicky signals from the inner ear, and space sickness disappears.

Mike Fincke has spent more fourth dimension in space than any other American astronaut—381 and a half days, spread over three missions. He has washed nine space walks, totaling 48 hours. When his first station posting was unexpectedly moved frontwards in 2004, Fincke became the commencement U.S. astronaut to become a father while in infinite. Mission Control patched him through to his wife's cellphone while she was in labor.

For Fincke, in that location'southward null similar the flying. "At that place is sheer joy in it," he says. "Just sheer joy in flight in space. You lot tin can accept the most serious fifty-year-old curmudgeon and put him into orbit, in nix‑M, and he'll smile, he'll laugh, he'll giggle."

Fincke has degrees from MIT and Stanford, and graduated from the U.S. Air Forcefulness Exam Pilot School before becoming an astronaut. He's disarmingly communicative compared with the stereotype, unable to suppress his exuberance about his chore, even subsequently eighteen years. In 2011, he participated in a video call between the Space Station and Pope Bridegroom XVI in Vatican City. At the end, Fincke launched himself directly upwardly out of the video frame, inspiring the Italian press to joke about Christ'southward Ascension. "We even made the pope express joy," Fincke says.

"A niggling button with your large toe will accept you halfway beyond the station. Information technology's like existence Superman—with just the castor of a finger. Information technology does not get old, even after 381 days."

The very quality that makes space travel and so delightful too makes it invisibly dangerous. Goose egg‑Grand is harmful to the human being body in insidious means.

Significantly, astronauts lose os mass. Bones regenerate and grow partly in response to the work they have to exercise each twenty-four hour period. Without weight to support in space, the rate at which they brand fresh cells slows downwardly, and the bones sparse and weaken. A postmenopausal woman on Earth might lose i pct of os mass a yr. An astronaut of either gender can lose one per centum of bone mass a calendar month.

Marking Guilliams is the atomic number 82 strength-and-workout motorcoach for NASA astronauts. He works out of the expansive astronaut gym at Houston's Johnson Space Center, where the 43 agile American astronauts are based.

"Living in zero‑G is the equivalent of a long stay in a infirmary," Guilliams says. You lose muscle mass and strength. You lose claret volume. Y'all lose aerobic fitness, anaerobic fettle, stamina. "Spaceflight is difficult on the body. Menses."

It's hard on the trunk because it'due south so easy on the trunk. The antitoxin is vigorous, nigh relentless do while in space. The U.S. part of the station has 3 exercise machines—the seatless bike, a treadmill, and a weight machine known equally the ARED (avant-garde resistance do device) with a 600-pound capacity. Astronauts are scheduled for two and a half hours of exercise a day, half-dozen days a week, but most practice seven days a week. Do is considered so vital that NASA puts it right on the workday schedule, although some astronauts wake up early and practice it in their own time.

Mike Hopkins is a fitness buff, and he made a series of YouTube videos to show what astronaut workouts are like. The treadmill is the hardest piece of equipment to become used to, he says, because you take to be bungee-corded downwardly to provide the sense of weight to your trunk that a runner on Earth would have. "You run with a backpacking harness on, and that's fastened to bungees, and you tin can change the load, how hard it is pulling against you," Hopkins says. "I would endeavor to get upward to my trunk weight, simulating what it was similar to run on World. Just y'all're carrying that load on your shoulders and hips; it's like trying to run with a 180-pound pack on your dorsum."

Zero‑G doesn't make sweating any more pleasant. "You sweat buckets up at that place," says Hopkins. "On the ground, when you lot're riding the bike, the sweat drips off you. Upward there, the sweat sticks to you—you take pools of sweat on your arms, your head, around your eyes. One time in a while, a glob of it volition go flying off." The astronauts utilize large wipes and dry out towels to make clean off. "The shower was one of those things that I missed." Still, the sponge-bathroom method works just fine, and the station generally has a neutral olfactory property. Astronauts wear fresh clothes for a calendar week, which then become conditioning clothes for a week, which are then discarded with the residuum of the trash.

The focus on fitness is equally much about science and the future every bit information technology is about keeping whatever individual astronaut healthy. NASA is worried most two things: recovery time once astronauts return dwelling, and, crucially, how to maintain force and fitness for the two and a half years or more than that it would take to brand a round-trip to Mars, which President Obama has said he believes NASA tin can do past the mid‑2030s (although there is no detailed plan). Figuring out how to get to Mars safely, in fact, underlies much of what happens on the station. "If astronauts have a x percent loss of strength, of cardio capacity, how much does that impair their performance on station? Non much," says Guilliams. "But if you're going to Mars, that kind of loss could exist critical. What would they exist able to do when they land?"

We don't nonetheless sympathize all the implications of long-duration spaceflight. "Five years ago," says John Charles, of NASA's Human being Research Plan, "we had an astronaut on station all suddenly say, 'Hey, my eyesight has inverse. I'thousand iii months into this flight, and I tin can't read the checklists anymore.' " It turns out, Charles says, that all that fluid shifting upwardly in zilch‑M increases intracranial pressure. "Fluid pushes on the eyeball from behind and flattens it," says Charles. "Many astronauts slowly become farsighted in orbit."

In fact, the station is at present stocked with adjustable eyeglasses, then astronauts who don't commonly wear spectacles volition have them if they need them. Those who already habiliment glasses bring along extra pairs with stronger prescriptions.

Astronauts need precise, reliable vision, so its deterioration during spaceflight is hardly a small-scale problem. And it'due south a particularly humbling one. NASA has known virtually the eyesight outcome for decades. "We saw this on Skylab"—the starting time U.S. space station, which intermittently housed astronauts for up to iii months at a fourth dimension from 1973 to 1974—"and on the shuttle," Charles says. The importance of it just wasn't clear until astronauts were regularly spending months in orbit. And at the moment, NASA doesn't know how to fix it back on Earth. Bone mass, muscle mass, claret volume, aerobic fitness all render to normal, for the most function. But astronauts' eyes do non completely recover. Nor do doctors know exactly what would happen to eyesight over the course of a mission iv or five times longer than those of today.

"Nosotros're not watching annihilation else as significant as this right at present," Charles says. In March, the longest mission ever for an American astronaut volition begin: a total year on the station. (Iv cosmonauts have lived in space for a year or more, aboard the Russian space station Mir.) Before tackling a two-and-a-half-twelvemonth trip to Mars, Charles says, "we have to meet if in that location are whatever other things we aren't anticipating—psychologically or physiologically. Nosotros have to see if there are any cliffs."

"Hey, Houston, this is Station. Expert morning. We're ready for the morning DPC."

That's U.S. station commander Steven Swanson, hailing Mission Command from orbit ane morning last July to kickoff another fully scheduled space workday. For Americans of a certain age, those first 7 words—"Hey, Houston, this is Station. Good forenoon"—remain packed with a sense of romance, take chances, and unassuming competence. The astronauts are flying with the stars; Mission Control has things in mitt on the footing.

On shuttle missions—there were 135, stretching from 1981 to 2011—Mission Control would wake the astronauts, radioing up a outburst of music to kickoff each day. The wake-up-song tradition stretches dorsum to Gemini, and its passing is meaningful, at least symbolically. The station is a permanent outpost, with a mensurate of independence. Then Mission Control doesn't shake the astronauts awake. They get upwards in their mini-staterooms well before any contact with Houston, and and then signal the beginning of the workday by radioing down to Mission Command. They too end the day, by signing off for the night. When the astronauts get prepare to plow in, they bladder through the station, switching off lights and endmost window shutters, to shade their sleep from all those sunrises. Mission Control does non normally radio the station during off-hours.

But it's a thin layer of independence, equally acknowledged in that side by side line from Swanson—"We're ready for the morn DPC." Every twenty-four hour period starts and ends with a daily planning briefing, during which the astronauts briefly check in with all five control centers around the world to talk virtually schedule glitches or pending maintenance, or wait alee to the next solar day. (NASA has a 2nd facility, in Huntsville, Alabama, to handle scientific inquiry; Moscow has a Mission Control for the Russian half of the station; and the European Space Agency and Japan's infinite agency also have their own 24-hour control centers.) The astronauts may exist rocketing around Earth at 17,500 miles an hour, x times faster than the average bullet leaves a gun, just they tin't escape regular meetings.

Although the astronauts live and work in the Space Station, they don't fly it or otherwise command it. That'south all done from Houston and Moscow. Mission Control monitors the station's position in space and adjusts it as necessary, using gyroscopes and thrusters; Mission Control also monitors all the onboard systems—electrical, life back up, IT, communications. A vast squad on the ground supports the station—more than 1,000 people for every astronaut in orbit. And while astronauts get to kick off the workday, the pace and rhythm of the solar day are unequivocally ready by the people on the ground. Life on the station is managed via spreadsheet: every infinitesimal of each astronaut's workday is mapped out in blocks devoted to specific tasks. When an astronaut clicks on a time block, information technology expands to present all the steps necessary to perform the job at hand—whether it'southward conducting an hours-long experiment on the beliefs of fire in nix-M or stowing supplies from a cargo transport.

In its own mode, the schedule tin can exist a source of freedom for astronauts who surrender to it, simply it is also a symbol of a certain tyranny. Science experiments, maintenance tasks, cargo-vehicle arrival and departure: all are ready from the ground. Each astronaut's schedule has a red line that slowly shifts beyond the laptop screen, left to right, showing the electric current time and what the astronaut should be doing at that particular moment. "The red line, no matter what I do, it only keeps moving and moving to the right," groans the astronaut Garrett Reisman, in a tongue-in-cheek YouTube video he recorded in space. "I can't finish it!"

Life in space is so complicated that a lot of logistics accept to be off-loaded to the ground if astronauts are to really practice anything substantive. Only building the schedule for the astronauts in orbit on the U.S. side of the station requires a full-fourth dimension team of l staffers.

The schedulers get input and priorities from everyone—what is the point of a particular six-calendar month mission? What scientific experiments will exist done? What cargo ships will visit? What maintenance tasks are necessary? Getting each individual item onto the schedule requires detail and coordination. For a particular experiment, what equipment and tools are required? Where are those things stowed? How long will setup take? What steps will the astronaut need to follow to conduct the experiment? Will enough power be available at that fourth dimension? Volition the experiment go in the way of what some other astronaut is doing? Who are the investigators on the ground? Will they need video observation? Is there sufficient bandwidth for all the video and sound being used at a given moment? Each twenty-four hour period has dozens of individual activities requiring that level of planning, which begins 18 months out.

Highly educated, highly motivated astronauts stop up doing 1 task after some other, all day long, some of them fun and intellectually challenging (doing research with basis-based scientists), some of them ho-hum (recording the serial numbers of the items in the trash before sending them to be burned up in the atmosphere). No one signs up to fly through space in order to empty the urine container or swap out air filters. But of course even the research is commissioned and directed by other people—the astronauts are just highly skilled technicians.

NASA struggles to rest the independence of its astronauts with the desire to go on them on schedule. In the anonymous diary study conducted past Jack Stuster, work was the most frequent topic raised by astronauts in their journal entries, and when Stuster analyzed the piece of work entries, scheduling was the second about often discussed topic, after simple descriptions of tasks.

"Only 30 minutes [scheduled] to execute a 55-step procedure that required collecting 21 items," wrote an astronaut. "It took 3 or 4 hours." Another wrote, "It has been a pretty tedious week with tasks that were clearly allotted likewise little fourth dimension on the schedule. Talking to [a Mission Command staffer] today, I realized he just doesn't understand how we work up here."

Astronauts need precise vision, so its deterioration during spaceflight is a meaning, and humbling, problem.

That'southward a pretty standard complaint, of course: Soldiers at the front line have one impression of how the war is going; military headquarters has some other. Sales reps in the field see the products and the customers 1 way; the vice president of sales sees them differently. In part because of the intendance NASA takes picking astronauts and assigning them to crews, and in part because the astronauts appreciate the need to work together, they all report getting along well, and beingness able to chop-chop resolve minor disputes. But at the aforementioned time, from their perspective, information technology's difficult for NASA'due south Space Station basis staff to sympathize life in space. As with anything else, the privileges and joys of working in space don't neutralize ordinary office politics.

Stuster's study has a whole subcategory of diary entries devoted to "praise inflation," a phenomenon whereby the astronauts feel compelled to pass out "profuse compliments, fifty-fifty when undeserved," to ground personnel, "and a general avoidance of criticizing ground personnel for deficiencies, real and perceived." The tradition of praise goes back to the moon effort—when the astronauts were bathed in celebrity, and worked hard to pass that on to the army of technicians who fabricated the mission possible.

But on the station, it can sometimes grate. Wrote 1 astronaut: "I feel that the footing has oft fabricated my life more difficult here, thus making information technology hard to hand out praise on such a frequent basis." Virtually anyone who has always had a job can imagine the eye-rolling that goes on, both in Houston and on the station: What are those guys up in that location/downwardly there thinking?

For the most part, such sentiments go unexpressed. Peggy Whitson, a veteran of two vi-month station postings, was the chief of NASA's astronaut office—the astronauts' directly dominate—from 2009 to 2012. Advice was something she paid close attending to, on both ends of the radio. "One affair I can tell you," Whitson says. "Sarcasm does not piece of work in space travel."

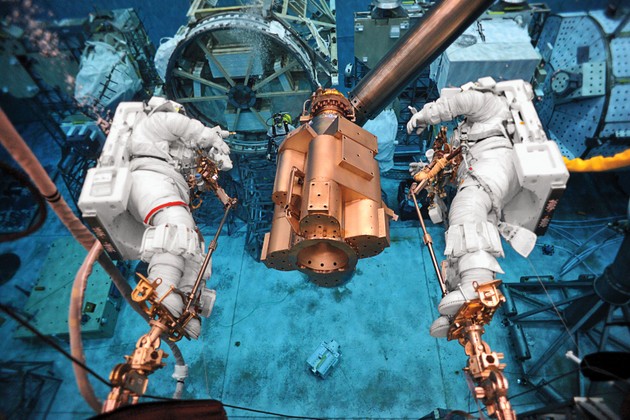

Scott Kelly and Tim Kopra are continuing dorsum-to-back on a steel platform in July, outfitted in NASA infinite suits. A yellow crane slowly lifts the platform, swings information technology out over the surface of a huge swimming puddle, then lowers the astronauts into the water. Kelly and Kopra are going to spend about of the 24-hour interval—six hours—underwater, doing a practice space walk in the puddle, going through every step of replacing part of the Space Station's robotic arm. It's a maintenance task they will do in space side by side November.

Kelly and Kopra spend xxx minutes getting latched into the suits, each of which weighs 230 pounds empty. A beau astronaut, Kevin Ford, is watching. "Run into how each astronaut has three or four guys helping him?" says Ford, who was the commander of the Space Station for 4 months in 2012 and 2013. "On station, information technology's but one guy suiting up two astronauts. The procedure to get into the space suits and out the hatch is a 400-step checklist. And you don't want to skip too many of those steps."

Iv hundred steps, just to get i astronaut set up to float into the station's air lock and prepare to egress. Before a NASA astronaut starts the first minute of a space walk, he or she has spent iv hours getting into the adjust and checking it over. And long before that, the astronaut has rehearsed that specific six-to-eight-hour infinite walk five or more times on World, in the pool, which NASA calls the Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory.

Nothing captures the strange contradictions of modern spaceflight as well equally spacewalking—shoving off into infinite with simply your wits and training, sealed into your one-person spacecraft. An EVA (extravehicular activity) is, for almost all astronauts, the ultimate professional person challenge and the ultimate thrill ride. When yous're outside the station, you are literally an independent astronomical body, a tiny moon of Earth, orbiting at 17,500 miles an hr. When y'all look at Earth between your boots, that first step is more than 1 1000000 feet downwards.

Merely spacewalking is also a window into how dangerous space is, how a single connector not properly mated tin can lead to disaster, and how NASA has grappled with that adventure by wringing all the spontaneity, all the surprise, out of it. That's why every scheduled space walk is scripted, and then rehearsed and rehearsed and rehearsed in a pool big enough to immerse 2 infinite shuttles.

Working in space to construct or repair a spaceship that weighs 1 million pounds is so challenging that the station's exterior elements accept a remarkable applied science feature: although the station is made upwardly of more than 100 components, with a surface expanse spanning almost three acres, most bolts the astronauts piece of work with are a single size. That way astronauts well-nigh never accept to worry nearly irresolute sockets. Imagine constructing a whole edifice that way. All the scripting, the rehearsal, the pattern considerations—life in space isn't just stranger than ordinary folks realize; it'south harder. Harder even than NASA has ever imagined.

The agency originally promised that space shuttles would wing at least 25 times a year. In actuality, the shuttle programme averaged fewer than five flights a year; in the acme yr, 1985, the shuttle flew nine times. It was President Ronald Reagan, in his 1984 Land of the Union speech, who directed NASA to create and permanently staff a infinite station, which he predicted would "permit quantum leaps in our enquiry in science, communications, in metals, and in lifesaving medicines which could exist manufactured only in space." NASA's original vision for the station was as ambitious as information technology had been for Apollo or the shuttles. The station was to take vii major functions—it was to be a research lab, a manufacturing facility, an observatory, a space transportation hub, a satellite-repair facility, a spacecraft-assembly facility, and a staging base for manned missions to the solar organization.

30 years after, just one of those functions remains: enquiry lab. And Reagan's aspirations still, no one today is using materials or medicines invented on the station, let alone manufactured in that location. Currently, about 40 percent of the station's commercial-research capacity is unused—in role, perhaps, because some companies don't know information technology's available; in office considering others aren't certain how cipher-G enquiry would exist worthwhile.

The space walk is in some ways a microcosm of the whole infinite-station program: difficult, monumental, and strangely tautological. Astronauts walk in space to maintain and repair the Space Station, so that future astronauts will have a base to wing to. As the station runs now, with a coiffure of three on the U.S. side, virtually two-thirds of the work washed by each astronaut each twenty-four hours is devoted merely to maintaining the station, handling logistics, and staying salubrious.

NASA has always said that understanding how to live and work in space for long periods was itself a central purpose of the Space Station. But without a road map from the White House and Congress for where human spaceflight is going, that function of the mission can seem round, especially at $viii meg a 24-hour interval.

And yet we've always had an odd standard for judging the cost and the value of manned space exploration. As information technology happens, the price to run and sustain the Space Station is virtually the aforementioned as the cost to run a unmarried U.South. Navy aircraft-carrier battle group. We take 10 aircraft carriers at sea, with 2 more nether construction. And while an aircraft carrier at sea is a hive of nonstop activeness, that action is arguably just every bit circular equally what goes on in space. Information technology involves maintenance and routine operations and practice for fighting that most likely will never happen.

Infinite makes usa impatient. We're impatient for things to become smoothly, every bit if spaceflight should already work every bit infallibly as a flight to Dallas (witness the surprise in October when a supply rocket headed to the Infinite Station exploded 15 seconds after launch). And we're impatient for a render on investment, as if going to space couldn't possibly exist worthwhile unless it rapidly becomes a commercial bonanza.

We fly in infinite because of human ambition, considering cipher tests our power and character similar stretching ourselves beyond what we can do now. And we fly in space because space is the 8th continent. Thomas Jefferson didn't simply make the Louisiana Purchase; he dispatched Lewis and Clark to tramp the terrain and report back. Nosotros wing in space as curious explorers now because ane day we may need to fly in space, equally miners or settlers. The arguments for a manned infinite program are familiar. Just their familiarity doesn't reduce their forcefulness.

We may eventually need resources from asteroids or the moon, depending on how we manage the resources we've got hither on Earth. We may somewhen need to become a multiplanet species—either because we literally outgrow the Earth, or because we damage it. Or we may simply want to become a multiplanet species: one 24-hour interval, some people may adopt the empty blackness silence of the moon, or the uncrowded crimson dazzler of Mars, just as they preferred Oklahoma to Philadelphia in the 1890s.

These are long-horizon ideas—centuries-long. Even and then, what's missing from them is a sense of how difficult living, working, and traveling in space nonetheless is, and how long we may demand in order to change that. Nosotros're still at the beginning of the space age. More people tin fit on a unmarried commercial passenger jet, the Airbus A380, than have been in orbit. The Space Station's nigh important purpose may plough out to exist didactics us how to begin to make life in space more practical and less unsafe.

Almost anyone you talk with near the value of the Infinite Station somewhen starts talking virtually Mars. When they practise, information technology's articulate that nosotros don't yet have a very grown-up infinite program. The folks we send to space still don't have any real autonomy, because no one was imagining having to "practice" autonomy when the station was designed and built. On a trip to Mars, the distances are so great that a single vox or due east‑mail service exchange would involve a 30-infinitesimal round-trip. That i modify, among the yard others that going to Mars would crave, would alter the whole dynamic of life in space. The astronauts would have to handle things themselves.

That could be the real value of the Space Station—to shift NASA's man exploration programme from entirely World-controlled to more astronaut-directed, more democratic. This is non a high priority now; it would be inconvenient, inefficient. Simply the station's value could be magnified profoundly were NASA to develop a real ethic, and a real plan, for letting the people on the mission assume more responsibility for shaping and controlling information technology. If we have any greater ambitions for human being exploration in space, that's as important as the technical challenges. Bug of fitness and food supply are solvable. The real question is what autonomy for infinite travelers would look similar—and how Houston can best back up it. Autonomy will not only shape the psychology and planning of the mission; it will shape the design of the spacecraft itself.

Learning to let astronauts manage their own lives in space is going to be as hard as any technology challenge NASA has faced—and it's an element of infinite travel neither Houston nor American astronauts accept any feel with.

Between the Tv set shows, the movies, even the goofy videos from the Space Station, we take the wrong impression about life in space. We already take for granted something that is annihilation but routine. The astronauts experience this every day.

In a boring moment i solar day on the station, Mike Fincke decided it would exist fun to call one of his professors from MIT.

"Then the department secretary answers the phone—you know what they're similar," Fincke says. "She said, 'Well, he's really decorated right now.' Pause. 'Merely I guess because you're calling from infinite, I'll put yous through.' "

Source: https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2015/01/5200-days-in-space/383510/

0 Response to "Reagan Has Space Shuttle to Orbit Again to Sleep Lie by Dems"

Post a Comment